The Montreal Canadiens were born on December 2, 1909 in room 129 of the Windsor Hotel.

J. Ambrose O'Brien, a businessman and sports entrepreneur from Ottawa, with financial backing from business partner T.C. Hare, submitted the one thousand dollar National Hockey Association league entry fee and made guarantees for player salaries in the amount of $5,000.

The Montreal Wanderers had been one of the stronger teams in Eastern Canadian Amateur Hockey Association in 1908-09 and the owners of the club were upset that the ECAHA's other 3 teams - the Ottawa Senators, the Montreal Shamrocks, and the Quebec Bulldogs - had left them behind to create a newly formed league called the Canadian Hockey Association.

The CHA had been on created November 13, 1909 and was formed of the Ottawa, Montreal, and Quebec franchises, in addition to the Montreal National, and a team known as All - Montreal.

O'Brien meanwhile, had sports and arena interests in Renfrew, Haileybury and Cobalt and was sought out by Wanderers owners to form a new rival league to the CHA. Included in their ideas, was one for a Montreal based team comprised mainly of french speaking players, to counter the same idea of the CHA's Montreal National. It would be called the Montreal Canadiens, and their colours would be blue and white.

There was one small problem, these Montreal Canadiens had no arena to play in.

The issue was solved by the Wanderers, who wanted this new league to work out in such a bad way, that they would share their home rink, the Jubilee Arena, with the Canadiens.

So the NHA was born, with the Canadiens joining forces with the Renfrew Creamery Kings, the Cobalt Silver Kings, the Haileybury Comets, and of course, the Wanderers. The Canadiens and the NHA, in its rivalry with the CHA, endured a difficult birth with several false starts.

After part of the initial schedule was remade and finally scrapped, the NHA accepted, or conspired to lure as the theory goes, two additional franchises from the CHA - the Senators and the Shamrocks - and began the season anew in January of 1910.

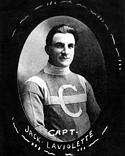

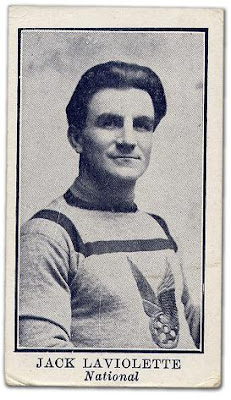

After part of the initial schedule was remade and finally scrapped, the NHA accepted, or conspired to lure as the theory goes, two additional franchises from the CHA - the Senators and the Shamrocks - and began the season anew in January of 1910.Jack Laviolette, a star player with the Montreal National of Federal Amateur Hockey League, the Michigan Soo Indians of the International Hockey League, and the Montreal Shamrocks of the Eastern Canadien Amateur Hockey Association, was regarded as one of the brighter hockey men the city of Montreal had in the early 1900's. He was brought in by owner O'Brien and teamed with secretary treasurer Eddy McCaffery in forming the group of players that would comprise the inaugural Montreal Canadiens team.

Laviolette, in addition to being manager, would also serve as the team's best defenseman and captain. He completed the task of getting players in place in less than one month.

Born Jean Baptiste "Jack" Laviolette in Belleville, Ontario on July 27, 1879, he moved with his family to Valleyfield, Quebec at age 12, where he developed a love of the game of hockey on his best friend Didier "Cannonball" Pitre's backyard rink.

Pitre, another defenseman, would become Laviolette's first signing to the Canadiens as he outbid the National for his services. It was quite a coup for the team, and the signing involved outracing the National's agent by train, who was also on the way to scoop up Pitre.

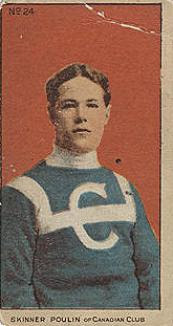

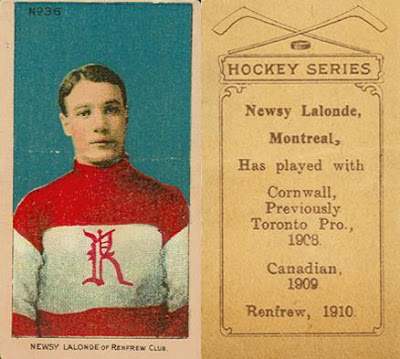

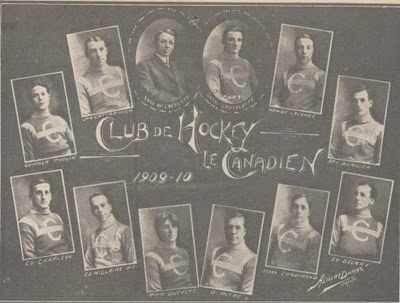

Soon after, Laviolette added Jos Cattarinich in goal and Newsy Lalonde in the rover position. The team's starters were rounded out by Ed Decary at center, with Arthur Bernier and Georges "Skinner" Poulin on the wings. Seven other players would suit up for Montreal in the restarted 12 game official season and they included Joseph Bougie, Ed Chapleau, Edgar Leduc, Edward Millaire, Patsy Séguin and goaltenders M. Larochelle and Teddy Groulx.

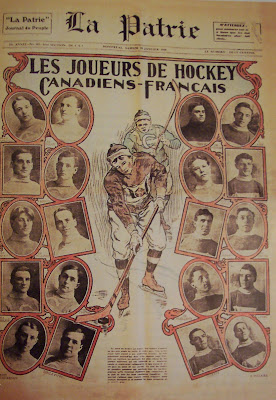

On a team photo handout of the day that featured the composition of the team, are two players named Rick Duckett and Noss Chartrand. There is little data pertaining to the standing of these players who were likely victims of the earlier season's false started schedule.

Laviolette, McCaffery, and O'Brien did much financial wheeling and dealing in aquiring several of their players, and certain transactions were contested with threats and lawsuits. After having stolen Pitre from under the National's nose, he targetted the services of Lalonde and Decary, and then moved on to All - Montreal for Poulin, all of whom where under contract.

With much of this contested in court, the Canadiens made headlines in local newpapers prior to having played their first NHA game.

Edouard Lalonde, was already known as Newsy by the time he arrived on the Canadiens scene. Born in Cornwall, Ontario, on October 31, 1887, the 22 year old Lalonde would quite rightfully become recognized as the Canadiens first true star player. Lalonde's on ice style made him the original "Flying Frenchman".

On January 5, 1910, the Canadiens beat the Cobalt squad 7-6 in overtime, with Lalonde scoring twice in what unofficially became their first ever game. Shortly after, the CHA was dissolved, and hence the Shamrocks and Senators, along with some of the league's better players, were absorbed into NHA.

It is not known how many games the Canadiens had played prior to the schedule being quickly revamped. The prior games played were shelved from the record and there exists little documentation today that details the false start.

The Canadiens restarted the season on January 19 and Lalonde recorded the team's first goal and hat trick in a loss to Renfrew. Both the Canadiens and Wanderers would play their local games at the Jubilee Arena, at the corner of Ste. Catherine and Malborough in the Westmount section of downtown Montreal. The Canadiens would lose the first four games in its history before beating Haileybury 9-5 on February 7, in front of a hometown crowd 3,000 strong. Pitre, the team's highest paid player at $1,700 per season, scored the winning goal.

Pitre would also score the winning goal in the Canadiens only other win of the 1910 season, registering a hat trick - a first for a Canadiens defenseman - on March 11 in a win over the crosstown Shamrocks. The game in itself was an oddity of sorts, as Canadiens starting goaltender M. Larochelle was tossed from the contest for vehemently arguing a goal with officials. Laviolette would take over in goal himself, thus becoming the first player coach to be credited with a win. Larochelle, who has no other Canadiens appearances to his credit, would not return. He has henceforth disappeared into mysterious Canadiens lore.

At the onset, the Canadiens were a bleak on ice, and off ice proposition. After three games, Laviolette passed the manager's hat to goalie Cattarinich so that he could concentrate his efforts on other duties involving the team while continuing to play.

Several events and strange occurances would mark the Canadiens initial campaign. Montreal would suffer its worst loss in history in this season on February 26, via a 15-3 pounding at the hands of the Haileybury Comets. In that game, Alex Currie and Nick Bawlf would become the first players to score 6 and 5 goals respectively against the sadsack Canadiens.

Finances were a problem for the Canadiens as well, and on March 9, prior to a game against the Wanderers, the Montreal players went on strike. Angered at not having been paid for their previous game, the players were convinced by Laviolette - who pointed to an arena full of possibly disappointed fans - that they would receive full renumeration for their services as soon as the gate receipts were counted.

The Canadiens would finish out the schedule in last place with a record of 2-10, scoring 59 goals and allowing an even 100. The following season, only Lalonde, Pitre, Laviolette, Bernier and Poulin would return.

In his first NHA season, Lalonde would score 38 goals in 11 games to win the league's first scoring title. He scored 16 of those in 6 games with the Canadiens before being "lent" to the Renfrew squad where he would add 22 more in the season's final five games. The move was done primarily to strengthen the O' Brien owned Creamery Kings in a Stanley Cup bid.

O' Brien was the big mover and shaker in the initial days of the NHA's first steps. In addition to the Canadiens and Renfrew, he also had ownership of the Haileybury and Cobalt franchises, and donated the league's first championship trophy - the O' Brien Cup.

Despite O' Brien's help, Renfrew would not manage its Cup goal, and the NHA championship and the Stanley Cup would become property of the Montreal Wanderers in 1910.

The Wanderers, led by stars Ernie Russell, Harry Hyland and goalie Riley Hern defeated the Berlin (now Kitchener) Union Jacks 7-3 in a one game Stanley Cup challenge held March 12, 1910 at the Jubilee Arena.

Ownership of the Stanley Cup at this time in hockey history is very different than it is known as today. As it was created to be a challenge cup, rules governing who could compete for it and how were in constant evolution until the bowl become property of the NHL.

The 1909 Stanley Cup champions were the Senators, then of the ECAHA. Ottawa had been awarded the Cup as league champions, and it was too late in the season for them to accept an outside challenge from the Winnipeg Shamrocks. While Ottawa partook in its first NHA season the following calendar year, it twice successfully defended its title in a pair of total goals games in January of 1910 against the Edmonton Eskimos and a team from Galt.

Though the Senators had twice defended their title, the team's name is inscribed on the bowl just once. Wheras other squads multiple wins within a 12 month period are duly recorded, there seemed to be little operative practice of consistency for inscriptions on the bowl.

Hockey in 1909-10, grew in often conspicuous leaps and bounds, and the Canadiens inaugural season mirrored the game's fast changing times.

The team's owners were sometimes suspect, often perceived by the public at large as simply money men cashing in on the sport's rise in popularity. As many of them were involved in boxing, horseracing, and gambling rings, hockey often suffered from the perception of it being nothing more than a violent mug's rackett. And it truly was!

Owners bought and sold teams quickly. Player's rights were fought over considerably. Local rinks gate receipts were questioned. In short, every variety of legal standing regarding the game had its share of dubious moments. Owners took advantage of players naivity, and the sides barely trusted each other.

That the Canadiens survived all of this, team name and origin intact, is quite a feat. They would have more than their share of trials and tribulations in their early going, but on the backs on great visionairies and proud players, they would outlast city rival teams through a multitude of ups and downs over the coming decades.

In all the fuss and flux, it would be the constants that remained from year to year that would bring about allegiance in the locals.

Laviolette and Cattarinich were emotionally invested in the team. Players such as Lalonde, Pitre, - stubborn as they came - and other mainstays to come, helped reinforce the team's humble foundation and build the sport in Eastern Canada.

Newsy Lalonde would leave his mark on the NHA and NHL, as much for his scoring exploits as he would for his temperament. A controversial figure of sorts, who was known at the time to have been making more money as one of the nation's best lacrosse players, Lalonde never hesitated to refuse his services when he felt he was being taking advantage of financially.

After the 1910-11 season, he jumped to Pacific Coast Hockey League's Vancouver Millionaires for more money. He was back in a Canadiens jersey the following season. Two seasons later he was sold / traded back to the Millionaires, but refused to report, causing the Canadiens all kinds of headaches in player and money transfers.

Regardless of his stubborn nature and his principles, Lalonde would be regarded as one of the NHL's early greats. He won six scoring championships across four leagues in his day - 2 NHA, 2 NHL, 1 PCHA in 1912, and 1 OPHL in 1909 - and would remain associated with the Canadiens as a player until 1923 when he was dealt to the Saskatoon Shieks for $3,500 and Aurel Joliat after a contractual squabble with then manager Leo Dandurand.

During his 12 seasons as a Canadiens player, Lalonde had been captain for eight of those years and its coach for 6. He played his final NHL game as a member of the New York Americans in 1927 and retired in 1929 after a year with the Niagara Falls Cataracts.

By 1932, he had patched up differences with Dandurand and returned to coach the Canadiens once more for two and a half seasons during some lean years for the club.

Pitre, a giant of a man for an early hockey player, had the on ice temperment of a teddy bear. He would play 13 of his next 14 hockey seasons in a Canadiens uniform, outlasting his sometimes rival team mate Lalonde by one season. A fast skating strong man with a reknowned hard shot, Pitre was one of the early game's better offensive defenseman at a time when the position was much less defined than it is today.

Laviolette would suit up for the Canadiens until 1918, when a car accident would end his career.

Cattarinich would not play for the Canadiens beyond the 1910 season. He would later team with Dandurand and another local businessman named Louis Letourneau to purchase the Canadiens.

For the 1910-11 season, Cattarinich would find his replacement in goal, and his discovery had a profound effect on the future of the Montreal Canadiens franchise.